Want to hear more from the actors and creators of your favorite shows and films? Subscribe to The Cinema Spot on YouTube for all of our upcoming interviews!

Managing editor & film and television critic with a Bachelor's of Arts in English Literature with a Writing Minor from the University of Guam. Currently in graduate school completing a Master's in English Literature.

My interview with the filmmaker, Polaris Banks, took place on Monday, March 8th at 10:00 pm CT. His independent short film, Reklaw, premiered at the South by Southwest (SXSW) film festival the following week. This article presented here is our conversation.

Warning: Some minor spoilers ahead for those unfamiliar with the story and/or have not yet seen the film!

Introducing the Filmmaker and His Short Film

Polaris Banks: I’m Polaris Banks. I’m the director of Reklaw and Casey Jones, and Reklaw is screening at South by Southwest this month in the Midnight Shorts category.

John Tangalin: What is your film about?

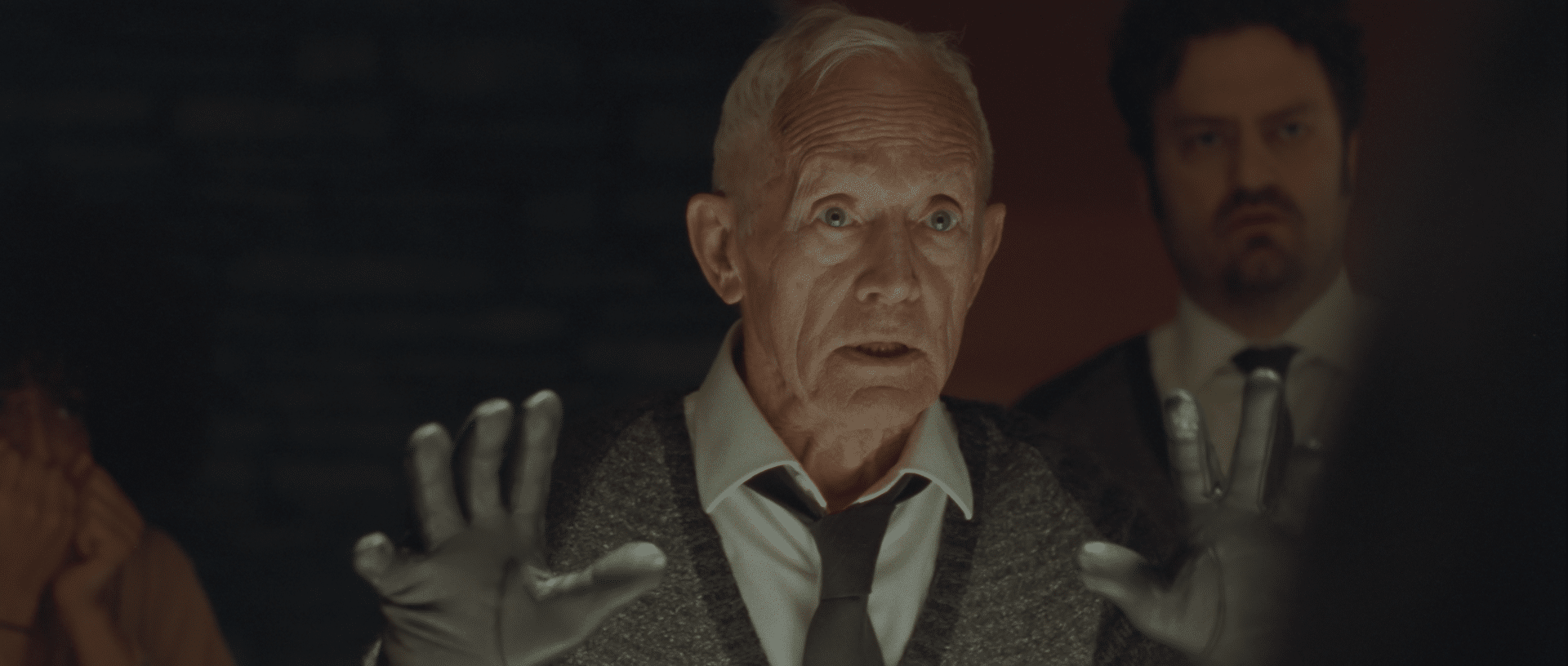

PB: It’s about a group of … altruistic vigilantes, where the leader [Lott, played by Lance Henriksen] is a prosecutor who’s kind of regretted his role in the justice system. He’s decided to spend the rest of his life trying to get as many people out of prison as possible, and he’s deduced that the best way to do that is to just destroy evidence at crime scenes before the police get there. So he’s amassed this group of interesting, uniquely talented either ex-cons or whatever. You assume that — it’s not explicit, but you see it from the short [film]. They intercept 9-1-1 calls, destroy the evidence, and give the people who’ve committed the crime the choice to get away with it if they want.

A Little Background Information Behind the Film

That’s from the logic of our current justice system in America [that] puts people out of prison when they’re done worse than they came in. We have the three options: help them — the best option — actually rehabilitate them; do nothing — you know, let the world be as it is; or make it worse and actually create worse people and make crime actually elevate with our justice system, which is what the way things are.

But that’s just the vigilante side. There’s also a couple of characters … it’s their anniversary and they’re doing something that’s kind of risque … a crazy anniversary present that goes awry. One of them ends up thinking they killed the other. That’s when the 9-1-1 call is made and the Reklaw team comes in and intercepts, and it gets crazy from there. I don’t want to give away too much, I guess.

Inspiration Behind Reklaw

JT: I wanted to bring that up. I don’t want to spoil any details for people who are interested in watching this short film. What inspired you to write this story?

PB: I wrote it about five years ago as a feature. Then, I decided that I didn’t have an updated work sample. I still had some things I wanted to learn about shooting with higher budgets, working with more established talent, and stuff like that. So I condensed it into a 12-minute short that kind of doubles as a proof of concept too, now.

The Incident as Inspiration

But I had the idea way back when I was around 19, I guess. Someone attacked me on the street. I flipped off a car that honked at me in the middle of the night. They turned around and started swinging at me. I actually had a weapon on me … a knife that a friend gave me that he worked at a knife shop, and I ended up actually stabbing this guy. [It is] a kind of a crazy story but it just happened. I wasn’t thinking, and I was like, “Oh, I just stabbed a man.”

Anyways, I called the police and I got him an ambulance and all that, but he had already kind of fled the scene. They tracked him down and he was fine. He made it through with a punctured spleen or whatever. It got me thinking, speaking with the cops there who came to the scene. They were telling me that you can’t just stab anybody who takes a swing at you and that I could actually — if he died — possibly go to jail for manslaughter or something.

Research through Filmed Works

A few days later, I saw a documentary on TV about the justice system and about, specifically, maximum security. I saw how people are given such terrible choices there to either … have to hurt somebody or kill somebody to initiate in a gang or be the person that gets killed [in] the initiation, and I realized how terrible th[ose] options are. [The documentary] talked about recidivism. Pretty much that’s when I decided, “Gosh, they should just let these people go. A lot of them did something not worth tanking the whole societal landscape over.”

I started to fantasize about how you could realistically get people out of prison, how you could destroy evidence, burn down an evidence locker, or hack computer systems or stuff like that. The idea just kind of filled itself out because there was so much material that came to mind. Since then, I’ve had a few other ideas for movies, but that’s the one that I’ve been most focused on because I have the full thing. Certain ideas just kind of put themselves together very fully.

Background on the Filmmaker

I transitioned the conversation into a brief discussion about himself and his milieu.

JT: Hence, this is why you labeled [the characters] as vigilantes, right? What inspired you to get into filmmaking?

PB: I have wanted to do it since I was seven years old. I used to really use my toys as a little kid, more as little storyboard things. And I positioned them and imagine what they would be doing and saying to each other. I was very quiet [as a child].

JT: I did that [too]!

PB: Exactly. The first movies I made were [with] LEGOs; they’re easy to stop [motion] animate. But I never considered anything else doing anything else. You know, when people come home from work, what’s the first thing they do? They want to watch TV, or see a movie, or listen to some music. Art always seemed to be the thing that makes life worth living and enriches people’s lives. My father and mother also produced theater, and my dad’s an actor and professional comedian. That was always an appreciation of filmmaking and art around the house, so it would be a pretty big 180 for me to go into real estate or something.

Inspiration for Diving into the Craft of Filmmaking

PB, con’t.: But it was always something I felt that I understood how to do. I would kind of deconstruct the movies my whole life and be like, “Okay, you take that shot, you cut it there, and put the light there”. I kind of figured it out [and] didn’t go to a film school [because] I couldn’t afford it, and I just took the little money I had that was set aside for college. (It wasn’t enough to actually go to college with, but my grandma put some money aside for us.)

I made my first [film, which was around] $30 grand … my first film that I actually put out there when I was around 22. Then, I’ve been shooting some other stuff and working on other projects, but this is my other big swing that I spent a lot of time and money on. I usually end up making things that take a while. I’d rather make one movie that I’m super proud of than a couple that I think are passable, you know?

Banks’s Filming/Writing Process

JT: You mentioned how you didn’t have that opportunity to get into film school. Was there was a hard challenge in your writing process because you didn’t acquire [the skills through there]?

PB: I did learn the hard way. I had the advantage of starting early, where I already made a feature when I was in high school. A two-hour movie [was] shot on the weekends, and I made everybody I know helped me with [it]. I even made more movies beyond that at that age. I kept shooting after high school, and we would just do several films [during] a summer, sometimes feature-length. None of them were really anything I was proud enough of to put out there and promote, but … we were trying our best, and then we’d make the next [film].

Doing that, you really do learn thoroughly what works, what makes you satisfied in what, where you were taking things for granted. By the time I shot Casey Jones I had already kind of failed enough and learned enough from movies I wasn’t satisfied with that I just kept on correcting and picking stuff up. But there [are] so many resources now on YouTube and behind-the-scenes documentaries.

“Learn By Doing”

PB, con’t.: I think most filmmakers, even if they do get to go to USC or something, they really don’t learn until their first movie after college. Then they make something or they try something and they go, “Oh, now I’m actually getting the experience,” because it’s totally something that you have to learn by doing. I think most filmmakers agree with that, where they say, “Put the book down and just start shooting because there’s so much that you’re not seeing here that you will learn immediately on set and immediately in your edit of what to do.”

JT: I like how you pointed out that you [took] from your own life experiences and also with documentaries, so it’s not always the film school route, right?

PB: Oh, so there’s so much great behind-the-scenes documentaries that people have been watching since they were kids. These little featurettes on HBO and stuff, they teach you so much, and there [are] so many great interviews, you know, with filmmakers and actors and writers and stuff.

Camera Work

JT: I just wanted to point out the cinematography. Your [director of photography, Robert Nachman] did so well because I loved how it was framed and even with you because you edited this film, right?

PB: Yes, I did. Yeah.

JT: What was your favorite part of filming, without giving too much away?

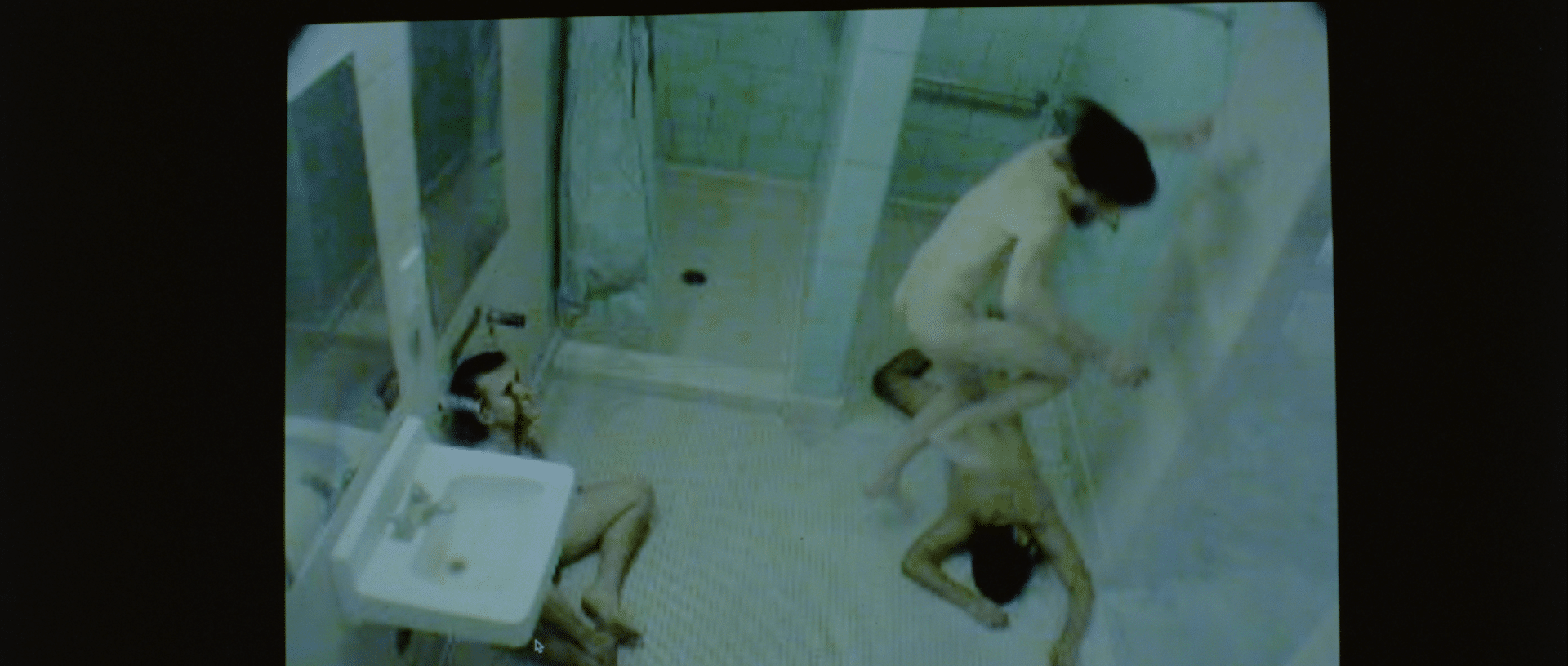

PB: I guess the part that made me the most like, “This is fun. Holy crap,” was actually what you wouldn’t think [it to be]. It was those shots in the RV when [the group is] watching prison footage. That’s actually me down there as a little speck with a bunch of stuntmen and extras playing prisoners. I just flew out to Utah with my best friend, Marty, and there’s an old jail there that you could rent for reasonably cheap. I did that actually a year before I shot the film [and] just was like, “Well, let’s get this out of the way,” because I had long hair. So I was like, “Well, we should do it where I look disheveled like I’m in prison.”

Stunt Work

PB, con’t.: I love doing the stunts where it was so fun to try and scramble up that wall and climb up on that TV stand or the part where like I’m stomping on that guy in the bathroom. Those are very fun. I like the stunts that I got to do in the kitchen scene. The whole movie is exciting to me, but if you’re asking which days are the ones that I’m just smiling the whole time and having a great time, it’s when I get to do something physical because so much of acting is just looking around and talking.

We rarely get to do anything where you can just forget there’s a camera there and worry that you’re wrestling a gun away from somebody or taking a swing at somebody. That’s partially why I played that role. … Misanthrope had so much dangerous stuff he had to do. I did audition other actors for it, and I couldn’t find anybody at my price range that I thought was as good a fit.

Also, it was so much more of a relief to me to put myself in danger instead of ask[ing] just some random person I cast, “Will you let this guy throw you into it into a cabinet or something? Or will you crawl up this wall where a bunch of people trying to pull you down?” You could really get hurt during a lot of the stuff that we did, and I didn’t have the money to really put down a lot of pads or do a lot of rehearsals, so a lot of the special effects in that movie are, “Trust me, I won’t get hurt. You can throw me around and fire the gun off”. That sort of thing.

Performances and Character Developments

JT: I want to get too into your character, but first I want to talk about [Lott, played by] Lance Henriksen. He had some really good lines in there as the voice of reason, in my opinion. What was it like working with him?

PB: Well, Lance was only there for two days. It was a 10-day shoot at the location, but the more expensive actors like Lance — he’s so established — I made sure to shoot all of his stuff at once, and there was no using the other actors to cut away to. I recorded them without Lance there and they were using stand-ins for his shoulders and reading lines to him. Shooting with Lance was just Lance all day. It was just like, “No more shots at you, Lance. Let’s do it again. Now we’re moving the camera to you more.”

Crafting Lott for Henriksen

PB, con’t.: It was interesting. We didn’t get to stop and talk about the character as much. We had a phone call about it, but we had to kind of feel it out while we’re shooting. Since we’re shooting on film, I couldn’t waste too much film just taking take after take. I did try to give him as many takes as necessary. I really sat there with him and we found it together, and I would be like, “Oh, in that line, he’s kind of regretting,” or, “He’s kind of searching,” or, “Here he’s callous,” and we would almost talk about it, shoot a shot, talk about it, shoot a shot. It was great.

Lance is such an experienced actor and so versatile that didn’t freak him out at all. He’s very good at rolling with the punches, whereas a lot of the other actors I’ve worked with really want to know what they’re getting [into]. They want to think about it all week and they wanna try it in the mirror and stuff.

Also, what he adds to that role is if you just look at it in the script, it can come off as condescending or professorial or kind of like bleeding heart — “Don’t hurt people” and that sort of thing. That’s the great thing about casting; you can supplement that by tak[ing] this character who’s like a pacifist and he’s like, “Be nice to everybody” and “Please guys,” and all that stuff, and you add this actor, who’s basically like a cowboy. Lance is just so true, so old-fashioned and sturdy, and knows what he wants.

Commending Henriksen For His Performance

He has no pretentiousness in him. There were several parts of the movie where — especially when he’s dealing with Tasha [Guevara, who plays Melissa] when he’s trying to console her downstairs — I had to tell him, “Be as kind and as gentle with her as you can,” and he’d be like, “I don’t have a gentle bone in my body. I don’t know how to do that”. He’s like, “I’ve never been a nice thing in my life,” but he is kind of a rough, no-nonsense guy in a fun way. It’s like casting a trucker as Mr. Rogers.

You get this really interesting combination that I think a lot of people can relate to and open up to. I don’t think anybody dislikes his character. He seems so genuine, but also not pretentious, which is what Lance brought to it, which is really great.

Landing Henriksen into the Role of Lott

The interesting part [about his performance] was that big monologue at the end. That was very important to nail, … one of the reasons I cast somebody more established. I think anyone who’s a good enough actor to make that moment work is already probably successful. I tried to audition some other people at lower levels of cost or [fewer] levels of success, [but] legitimately didn’t find anybody who can handle the material the way I wanted.

So I was like, “Okay, we’re going to have to carve out some more of the budget and get an established actor”. Lance was always in the top five, no matter … The second I started talking to the casting director, it’s always like, “Well, Lance Henriksen is an obvious choice. He works for it”. I tried some other actors. I piddled around, you know, maybe this guy, maybe that guy, but we ended up going, “Well, it’s gotta be, it’s just gotta be him. He fits so well.”

Banks Playing Misanthrope

JT: You brought up Tasha Guevara’s character, Melissa, and her scene with Michael Cortez [who plays Clifton].

PB: Yeah, the dinner scene.

JT: I think he and … the character Wylie [played by Michael Schnick. The viewer doesn’t] really see much of them. I want to get to Wylie in a little bit, but just to go back to your character. [He] has made some choices in his life, on-screen and off-screen. What are some of the risks that he takes, and what’s going on in his mind?

PB: They [the team] call him the Misanthrope. He’s a character that has a lot more backstory it’s in the feature[-length film] that we decided to allude to that you kind of get the vibes, but we don’t want to explain them too much. I think the audience gets his general thing that he’s someone who’s been to prison. [The team sees] the footage and they review some security footage for fun, really to watch old clips of the Misanthrope killing people. It’s a little morbid, but the characters are doing it just because it’s so interesting to watch him do it.

Introductory Details on Misanthrope

PB, con’t.: He’s so not what you’d expect where he’s this small [person]. He said it needed to be somebody kind of small and young and not formidable. He’s somebody who’s been put in prison who would be probably the victim, and he just doesn’t submit to anybody. He stopped caring about what anybody thinks or what society wants of him. He just has almost thrown his life away and gone, “Screw it, leave me alone. The end. If you mess with me, I will not think about harming you or whatever.”

Juxtaposing Misanthrope and Lott

PB, con’t.: It’s the opposite of Lott, and that’s part of the interest that lot has in Misanthrope”. Lott has had his life experience and decided that people matter. To make life have meaning is to treat everyone as if they have value, and forgiveness is really the best way to rehabilitate.

The Misanthrope has the exact opposite view, which is [that] “no one really matters. We’re all specks of dust. Kill anybody. Most people are dead anyway, whatever”. He doesn’t even want to participate in society enough to talk. He doesn’t even feel like communicating with other people unless necessary, and he’s kind of a person who has just lost interest in society.

Why Lott Joins the Team

PB, con’t.: The question is, “Why does he just go on, why doesn’t he just walk off a bridge and kill himself if he doesn’t care about life?” He doesn’t know either, and that’s part of the reason he’s interested in Lott; the Misanthrope knows there’s something he’s missing, and he’s not quite right about things. He’s going along with this [group. They] invited him in to do this thing because a part of him is still human.

The point of the end — I don’t want to tell you what happens — is the Misanthrope is given an opportunity. He sees the glimmer of that piece of him that’s still alive, that piece of him, and he sees the glimmer of it. But just because people are starting to see the light, it doesn’t mean they’re ready to change, and it doesn’t mean they’re ready to sacrifice the safety of people they do care about for this ideal. Donna [played by Clara Francesca Pagone] kind of plays into that.

Donna

PB, con’t.: Donna is a character we haven’t talked about yet, but she’s autistic and she’s kind of a savant. She doesn’t have the same social skills because of her autism that your average person does. It makes her somebody the Misanthrope actually identifies with a little more. They’re both a little outside of regular society. The Misanthrope, of all the people, is like, “I can kind of understand this Donna person”. He has an interest in her. He doesn’t talk to her much, but he maybe has some romantic feelings for her that he can’t get out of his head.

It’s really her presence that informs the ending that the Misanthrope might be willing to let a dangerous person go and put himself … and the other characters in danger, but it’s Donna that he’s like, “I’m not necessarily willing to do that”. I think that informs why a lot of people aren’t willing to give forgiveness and even reforming the justice system a chance; they go, “I care about my family. … I care about the things I have, and I’m not willing to put them in danger to maybe get this murderer, this drug dealer, whatever, rehabilitated.”

[Reklaw] is, on the surface, just a fun, thrilling ride, but it has these somewhat philosophical questions beneath it that the characters have to deal with, which is kind of interesting. If you want to be higher-minded, [then] you can watch it with that reading; but if you just wanna have a good time, you don’t have to.

From Where the Vigilantes Have Come

JT: I think you just answered my next two questions about Donna and what your character’s connections are to her. The way that I saw her, I didn’t see her as autistic. I felt like she had some trauma to her because Lott [asks], “Did you watch these tapes?” And she said, “Oh yeah, I saw. I saw them,” and then went on to his line.

PB: I think kind of where the characters are coming from — and I don’t make this explicit in the movie — but it is kind of assumed. Because Lott gets people out of these criminal situations and he’s amassed this little found family, and especially since you see the Misanthrope in prison, that you can assume that all of them were kind of plucked from institutional situations. The feature goes a little more into that. Bangs [played by Scott Allen Perry] and Wylie and the Misanthrope were all actual people who were either facing charges or were in prison who were released by Lott in some way.

Donna’s Use of Memory

PB, con’t.: Donna was institutionalized because of her age. Because she was a child in the ’80s, they actually put people with severe autism into institutions into a psych ward. That’s where [Lott] got her from, so … she’s also been an institutionalized person with trauma and that sort of thing, but there are some clues to her character in the movie that are not explicit.

[As] you said, that’s an interesting line where he says, “Did you see these tapes?” And she says, “I saw every one,” and he says, “If it’s in Donna’s memory, we don’t need to keep hard copies,” which is my little way of [saying], on the fifth viewing, if people want to catch on to that, is that Donna has a photographic memory. The way [the team gets] around carrying evidence with them or having anything that could jeopardize their operation is Donna just stores all [t]hat they need and is always kind of taking that. There’s just one part of the movie that kind of makes that a little explicit.

When they first go into the crime scene, you see her vision and it’s a series of stills that kind of create a composite picture. It’s something that the audience will mostly just be like, “Huh? Oh, whatever”. That’s my way of saying that Donna has this memory that stores things and is always kind of taking stuff in.

The Vigilantes’ Functions

PB, con’t.: [The team members] all kind of have these strange abilities. … Bangs knows forensics, and Wylie’s good with computers, and the Misanthrope is a physical character, and Donna has these unique abilities because of her autism. She also has some savantism that comes into play that she’s able to remember things and do things. She kind of actually runs their little cleanups, even though Bangs actually asked her, “Is everything good? Are we ready, willing to move on?”

There are these tiny clues about Donna, but I never really go into it as much because I, for some reason, like to hint at a larger world, but I don’t like to express it completely.

The Detail at the End with Wylie

JT: What happened to Wylie? Because when someone walks into the room and Lance says something, part of me felt like something happened to Wiley, or maybe Wiley just wasn’t aware of [the occurrence].

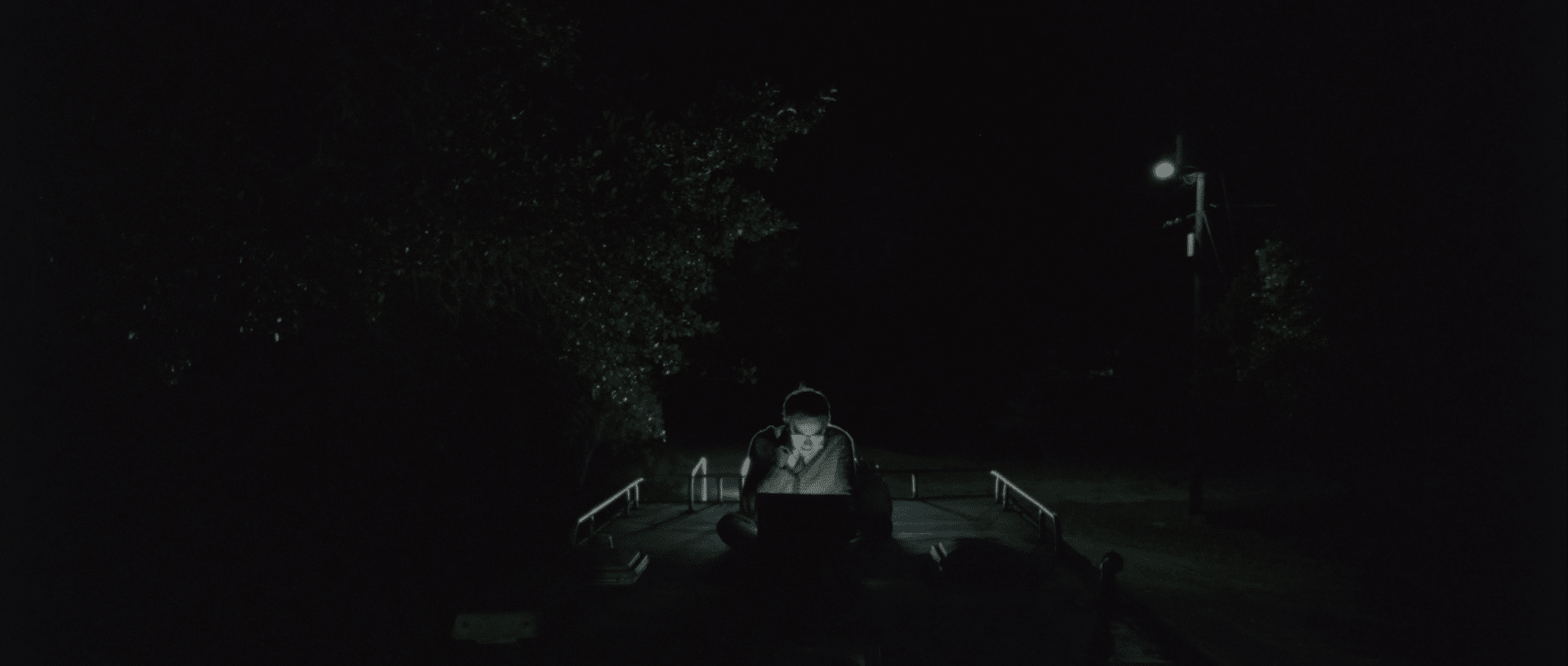

PB: This is … another little clue that people might miss or not. Right after the gunshots go off — where the Misanthrope grabs Marshall [played by Bill Stinchcomb]’s gun and starts firing into the air to eject the bullets so that he can’t use it as a weapon anymore — after all that commotion you actually hear Wylie in the earpiece say, “What’s going on in there?” I just had this little kind of line and you can hear it if you pay attention, but it’s not something. It pretty much answers that question; Wylie just missed this and it’s his first day. We alluded that he’s new to the team at the beginning.

Wylie on the RV

PB, con’t.: Bangs is kind of initiating by showing him the tapes and explaining the Misanthrope to him, so you kind of get the sense of Wylie’s new-ish. Then when he’s up on the RV monitoring for police, he says, “I don’t know if I’m supposed to tell you guys that,” so you get the sense that this is his first day. Especially also, when the call comes in, he says, “Oh God. We got one,” meaning he’s a little nervous. Those are my clues about him that he just messed up, he did not watch clear enough, and somebody just came and parked in the back [of the house] and came through.

JT: Right. There’s a patrol car coming by.

PB: Yeah. He’s monitoring the patrol cars, but he didn’t watch out for people just coming to the house and parking from the back street or the alley, which is why Marshall comes in through the back door. That would possibly [be] where Wiley didn’t notice, because he’s perched on top of the RV and he’s supposed to be scanning for anything, any threats.

Concealing Identities Through Masks

JT: I’m a graduate student and [am] looking into doing this Master’s thesis on superheroes and technology and the use of masks because [both] technology and superheroes wear their masks. In terms of your character group, they have their own masks, which [are] the shades or the glasses. You mentioned [this] with Donna and how she was seeing visions or specs of a memory.

PB: Yeah. She’s memorizing the room and making a composite. We did have to go to the spec vision because she’s wearing the glasses so it does look like binocular vision to kind of make that clear. Every time there’s a heist movie, you have to have some way to obscure their identity. It’s kind of one of the fun tropes of characters doing a team crime. You can see [this] in The Town, they wear the nun thing — it’s a great movie — and the president masks in Point Break. I’m always interested in what their masks are going to be and how they do it. It’s this fun opportunity to do a new one and then try and do something iconic.

Banks’s Inspiration Behind the Vigilantes’ Masks — Old School

PB, con’t.: I wanted to have a throwback feel to [my film] where, since we’re talking about the justice system and right and wrong, and the old style from the 20th century — the good guys stop the bad guys, the bad guys go to jail –, I wanted to subvert that and be like, “We’re going against … all these ideals about society and what’s good and what’s wrong. Our lead characters are good guys, pretty much terrorists. They’re letting criminals go free, and it felt very like a subversion of America. That’s partially why the movie has this kind of kitschy ’50s, ’60s through 66 kinds of design.

Also, I wanted to have to kind of play off of that. I wanted the team to kind of remind you of Mr. Rogers the [nicest] American person. [They] put on sweaters and wear something that a nice “father knows best” would have. I thought about the ’50s and some of their ways [that] they obscured the face; I remembered that they would have those novelty specs that you could put on.

Banks’s Inspiration Behind the Vigilantes’ Masks — Cartoons

PB, con’t.: I don’t know if you saw that episode of The Simpsons. That’s the first time I saw it as Homer’s on jury duty and he keeps putting on those fake eyeglasses so he could take naps. He’s like, “Oh, I listened to every word!” and I’m like, “Give me those!” I don’t remember where I initially got the idea, but I thought that would be so iconic to have these characters doing this stuff and having these kinds of dead eyes, especially Bangs with his lady ones which are kind of colorful and fun. It kind of turned out iconic where if I did a feature version, if that got made, I go, “We got to keep the eye specs. That’s classic [and] that’s going to be great.”

Banks’s Inspiration Behind the Vigilantes’ Masks — Film

PB, con’t.: When I’m designing characters, especially hero characters, I would want them to have a look that you could go as for Halloween. Even if it’s something that’s not necessarily a superhero, like a Coen Brothers movie, [where] people go as The Dude from The Big Lebowski. He had a signature enough look that you could go as him. I try to do that with every movie where I go, you should be able to cosplay as these characters, or else it’s not signature enough.

And there are a lot of seemingly normal movies, like Pulp Fiction, where I had a friend go as Uma Thurman, and she just wore the black bangs and had a little bit of blood there smeared and the white shirt, and I … completely g[o]t it immediately just from just these little details. It’s important to me. I want to do that with every movie that the characters have an iconic look.

JT: I think the glasses would be a way to replicate or make their own copy of the past, just to honor the past, right?

PB: Yeah.

Misanthrope’s Mask(s), If Any

JT: I think you did mention this earlier with Missy — [Misanthrope’s] nickname — and his mask. Is he hiding something in particular about himself [by wearing a metaphorical and literal/physical mask]?

PB: I guess he’s a mysterious character where you can project a lot onto him. To me personally, it’s not that he’s hiding stuff because people who hide things … care, they care what people think and they don’t want people to judge them, so to me, he’s not being generous with himself. He’s just going, “Yes, I have things to say. I have ideas, I have a personality, I have experiences, and I do not care to share them with you, I don’t care about anybody, I don’t care if I enriched your life, nothing matters.”

Establishing Missy’s Connection to Donna

PB, con’t.: He’s just not participating and he doesn’t feel the need to share himself with anybody except for maybe Donna. That’s why the only time in the movie where he interacts with someone charitably is when Donna forgets her earplugs. There is a saw going off and she has — [like] a lot of autistic people have — a sensitivity to sound and light, and it would really bother them to have these shrill noises.

[The Misanthrope] remembered to bring a spare pair of earplugs for her when you noticed she didn’t have them, and that surprises even Donna a little. She gives some kind of a look like, “Should I take these? What’s going on here?” It is in my opinion, him being not generous with himself, not willing to share himself in any way, not hiding anything too specific.

It’s also interesting … that they’re watching his prison footage and they’re watching him stomp on a guy while he’s naked in the bathroom, and he does not care. Bangs makes that clear, [saying], “Missy does not care. He will not even acknowledge that we’re here”. [Misanthrope]’s kind of a mysterious character. … Since I wrote the [script], I’m really interested to hear people like you talk about how he comes off without context. It’s interesting to me to hear you talk about it.

One Side of the Misanthrope

JT: I think for him taking out the glasses now that we’re talking about it, it’s like he is unleashed, like exposing himself, but not sharing himself with others in a way.

PB: Yeah, that really is the real him, the person who follows his base impulses of violence. I guess at that moment he is metaphorically like, “All right, screw all this. I’m doing it my way,” and there is that way of the Misanthrope. I believe he has kind of an almost unspoken deal with Lott, where he’s like, “I’ll do it your way. I’ll put on these glasses, I’ll help these people.”

It’s expanded/expounded in the feature that the Misanthrope doesn’t like owing anybody. He almost wants to force the relationship into a transactional one. When somebody does something charitable with him, he wants to be like, “You do something for me, I’ll do something for you. We’re not friends or anything like that, so he kind of makes this pact; “I don’t want to owe you anything, so I will help you with your little helping getting people out of jail thing,” even though inside, he also was a little curious about where that could lead him.

Misanthrope in Both Versions of the Reklaw Narrative

PB, con’t.: But there are parts in both the feature and the short film that he kind of throws that away and goes, “Okay, we’re doing it my way,” because something is in jeopardy, either his own possibility of going back to prison or Donna is in danger. Those are the parts where he goes, “Okay, I’m just going to snap this guy’s neck and we’re not going to this lovey-dovey shit. We tried that”. It’s this kind of opposites struggle between Lott and the Misanthrope, which I think actually expands into society where … if you’ve been talking politically or religiously or something like that, a lot of people are almost divided 50 and 50, where half of them are like I’m not gonna do this kumbaya crap.

Kumbaya

JT: That’s what Bangs says, that it’s actually kumbaya.

PB: He says, “Kumbaya” … a good little shorthand for “Uh-huh. I don’t want to do this”. … [Surely,] all of us have felt like both at different times where there are just days where we go, “Fuck it, I just want everyone who disagrees with me to just be dropped in a hole and they’re ruining the world and I don’t care,” and there are other days where you’re like, “I just need to reach them. I need to be charitable … to treat them as equals,” and we’re all struggling with it.

The Misanthrope and Lott are very representational of the extremes that are inside of all of us, on our little shoulders. And then we have some nuanced characters. Donna kind of draws her line at personal safety, when they have that argument during the fight scene. Her deal is pretty much, “I’m not willing to shake it. This guy seems like he’s very mad and he has a weapon. I’m not willing to do this nice stuff when somebody actually might kill me”. She’s very self-protective, and a lot of people are that way too like, “I will be nice up until the point that I am in danger.”

Bangs

PB, con’t.: Then there [are] people like Bangs who is interested in moral grayness where he’s like, “It’s neither the Misanthrope or you, and we should just be reasonable about this, and we can do this bad thing here but this nice thing [t]here”. He’s willing to kind of fudge the rules, whereas people with set morals don’t respond to that.

Psychopaths a lot, even real ones, but also characters that are in fiction, like Hannibal Lecter; they have rules, even the bad people. They’re like,” I have my rules, that this person I do not harm and this person I do, if they’re rude or whatever”. Dexter, those sort of things. They’re killers with rules.

Bangs kind of represents having no steadfast rules. It’s like everything is malleable. Everything is willing to kind of adjust, and he even has that kind of line that alludes to that when he says, “Sarcophagi one full, just to fun,” and Donna corrects his grammar and he’s like, “Live a little”. Bangs never follows any rule completely, which makes sense why he could end up on a morally ambiguous team of people doing something that could be wrong to a lot of people.

Banks realizes he’s been talking a lot during the interview, to which I told him that I had a lot to ask.

Reklaw’s Genre(s)

JT: Your film [is] categorized on the South by Southwest online schedule as a crime genre, mystery, and a thriller. You have a lot of genres going on … For me, picking out the lines, there are some hints of comedy in there where you mentioned the sarcophagi. I had to watch the film maybe three or four times. I think [during] the first two times, I missed the part where someone said that he died stiff.

PB: Right. And you can see his erection just briefly before. Yeah. You almost did pause the movie when you see his dead body to be like, “Oh my gosh, that was a funny part because we had to decide how big to make this erection under the sheet. I was like, “It’s gotta be big enough that they get what it is half a second”. But you’re right. There’s a lot of comedy.

When [given] a genre list of keywords when I’m submitting to a festival or putting it on IMDB or something, the [genre] that fits the most is pulp, where … as a genre is pretty much like whatever it is, it’s just salacious and interesting. It’s twisty, it’s turny, it’s got comedy, it’s got violence, it’s got mystery, it’s got sexual elements, but it’s also got drama. …. Just whatever gets the audience hooked and they want to turn the page, you know what I mean? That’s why … it’s really a pulp film. And I didn’t know how to talk about it either.

Cross-Genre

PB, con’t.: I would call it cross-genre a lot where … every moment is always two or three genres at once. There’s no moment in the movie that is fully serious, fully dramatic, fully action, fully comedy. And we had to play with that dissonance and that kind of subversion throughout the whole thing. For the sound design, for the art design, for the costumes and the casting, and the music especially.

Every time I would add a new element and in the process, I would go, “Okay, the actors are acting dramatic, so the art design has to be somewhat fun. This moment is very scary, so the lines and the music’s scary, so the lines to be comedic,” or “This is some comedy here, so we have to have something gross and horrific. We have some funny lines while [Donna]’s cutting up a leg and you see the guts in there.”

Every moment, even that time when she discovers a dead body and she screamed bloody murder, it’s also funny because he died with an erection. I never want [the audience] to have just a full one kind of way of experiencing the movie. Even the restaurant scene where you’re watching something that’s like crazy and sexual and perverse. [Melissa and Clifton] are treating it kind of giddy and it’s a little funny and weird, and it’s also romantic. They actually do love each other, and they’re treating each other with a lot of excitement.

Bangs As Source of Comedy

JT: Well, she consented to the [act].

PB: Exactly. They have just a kooky relationship, you know? I could go through the whole movie and really cite where one element is subverting the other. Bangs is a constant source of this, where no matter what is happening, he’s making jokes. Then there are certain times, even when he’s being honest and he’s like, “We’re in danger here, and this is crazy”. He’s still doing it in a funny way. I just always have to have those elements everywhere. But that’s why I say the movies kind of cross-genre. The closest thing I could really compare it to [is], because a lot of people say, Quentin Tarantino. I actually think more [of] something like Chuck Palahniuk where you watch something like Fight Club or something where it’s always —

I show the filmmaker my copy of Palahniuk’s novel, Fight Club on the shelf behind me.

PB: Oh, you got [it] on the shelf?

JT: Yeah, I have yet to read his other novels though.

Every Work is Never Just One Genre

PB: Yeah, so he likes everything to be a little darkly humorous as well as dramatic. Everything is a lot of things at once, and I think that’s honest to life because I’ve never been in a situation where something was happening that was all the way one thing. Even when somebody was breaking down crying a party was like, “Ah, this is funny and weird”. I think audiences really love having a lot of elements mixed together, but they’re very hard films to make because you can blow this so [easily].

There’s a lot of times I’ll watch a movie and I’ll go, “This does not belong in your kooky [context].” There are shows like Scrubs to me that I have trouble with where I go, “You just had the kookiest cartoon thing, and now you’re playing some indie-folk and expecting me to care about this woman dying of cancer. I can’t…you didn’t balance this right for me, personally”. But my favorite movies are the ones that do. That’s why the Coen brothers are so amazing is that they’ve never made a straight movie in their life. You know, Fargo is always a lot of things at once. I just love it.

“Sweater Weather”

JT: Just to add to the discussion on the comedy, you have … Bangs who says, when they get the call, says “It’s sweater weather, motherfuckers”. The way they say it just made me laugh.

PB: Yeah. I put that in the trailer because I was like this is our catchphrase. That was a funny line because that’s hard to translate in other languages. I translated the movie in a few languages so far and I’ll do more eventually, but that’s one where they always go, “Well, we don’t have the phrase because it doesn’t rhyme here and all that stuff.”

Translating the jokes into the whole movie really made me have to think about them and go, “Why is he saying it’s sweater weather?” I have to explain to them. I need something that is like, “He’s having fun. He’s calling to action, but he’s also being like the little shit by not taking this seriously when someone’s dead and all that”. There probably isn’t a 30-second period that goes on in the movie where there’s not something funny that you can laugh at.

Wrap-Up

At this point, I begin to wrap up the official interview with my final questions.

JT: Although this is a short film, I do see that you can go on from there. Is there a hint or an idea of a follow-up, like a sequel to Reklaw?

PB: I don’t have a short sequel, but I talked about it earlier. Kind of spilled the beans, but the short [film] is actually taken from a feature, and the feature has just so many more elements to the plot and twists and turns and all that. I just wanted to give an introduction to the concept of the characters, that they clean up crime scenes and intercept calls, they’re this weird team of people and the conflict between Lott and the Misanthrope and the moral quandaries that get themselves into.

The Much Larger Picture

PB, con’t.: But the feature … actually starts in prison, and the first third of it is how they get Wylie and the Misanthrope out of prison and introducing Lott and [the rest of the team]. Then the middle is more like the short film, where it shows their attempts at making their little system work and getting people out of prison and all that.

Then it gets darker, where they discover a serial killer that they actually come across, and Lott wants to treat him like anyone else. Lott wants to destroy his evidence and keep him out of jail too, and he’s like, “Everyone’s life is the same, and we don’t pick”. That starts to divide the team. Then the serial killer takes an interest in them because they’re destroying his work and it gets more complicated and dark from there.

But there are these two big plot points, which is what happens when they encounter somebody that possibly should not be kept out of prison and how they initially start getting people out of prison and form the team that [is] probably the better parts of the story that I couldn’t get through in a short, but I definitely want to explore in a feature.

The Meaning Behind The Characters’ Names

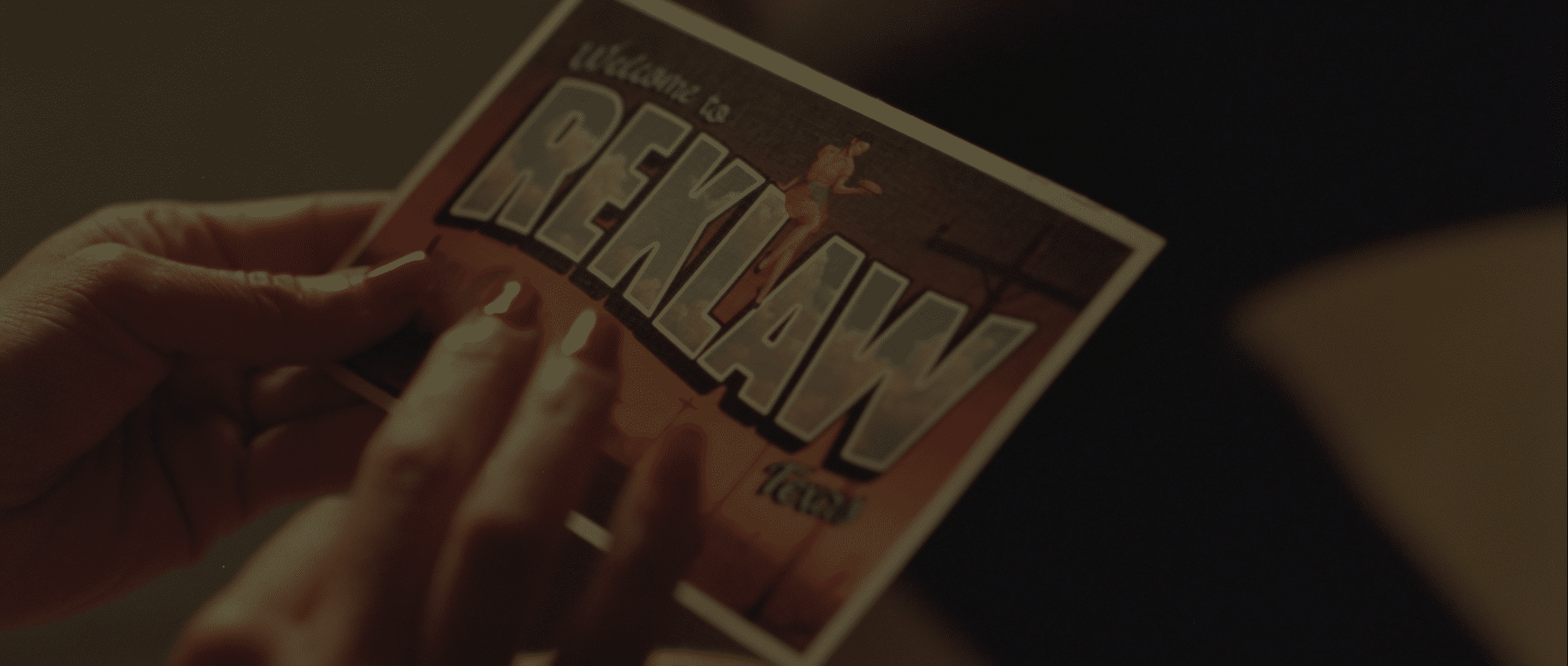

JT: Lott has a postcard that he gives to Melissa. What is in your version of Reklaw? What is Reklaw to you? He tells, he tells Melissa something. I won’t give it away, of course.

PB: It’s strange that the movie got its name. It’s hard to name characters, where anytime I’m making a movie, I go, “I don’t know, there are a million names. I don’t know”. I usually give myself parameters. [In Reklaw], the movie takes place in Texas and I’m from Texas. So every character’s name is actually taken from a Texas city, besides the Misanthrope because he doesn’t have a name. There’s a Lott in Texas; a Bangs, Texas, a Donna, a Wylie, Texas; even a Marshall, Clifton, and Melissa, Texas.

The Meaning Behind The Title

PB, con’t.: When I was doing that research, I saw the city Reklaw. And I was like, “Oh, it sounds like wrecking the law”. It’s weird … like my movie, and I looked it up. What that name is, is that they wanted to name their city Walker, Texas after somebody who found the city and it’s backward because there was already a Walker and they were stubbornly like, “Screw you, we’re keeping Walker. We’ll just reverse it. We’re not naming it, anything else”. I liked that … not only did Reklaw sound like wrecking the law. They usually say when somebody is released from prison or they don’t go to jail, they say [that] they walk. This guy is going to walk.

Get-out-of-jail-free Cards

PB, con’t.: Every [character] but Lott. I was like, “Whoa, that’s cool”. I actually had in the feature when Lott’s still kind of forming the team, the prison that they get the Misanthrope and Wylie out of is by Reklaw, Texas. [The team gets] them out and they get in the RV and they stopped there to have a meal and kind of talk about what they do.

Lott [will be] charmed by that postcard. He was like, “Reklaw. And he’s like, how many things you got? I’ll buy your entire stock of this”. [For] anyone who gets out of jail, he sends them a postcard, and on the back are instructions about either… “If you’re already in jail, [you] had to file an appeal. Now that your evidence has been destroyed from the evidence locker, or if you aren’t in jail, how to get out. Wait this amount of time, call it a missing persons [case]. Make sure this is destroyed. The postcard has some basic instructions scribbled down. If you want to get away with this, it’s up to you, and this is how you get away with murder or whatever you did”. The postcard kind of just represents kind of a golden ticket to actually getting your life back.

JT: Like, a get-out-of-jail-free card.

PB: “Get-out-of-jail-free card”. Yeah. I should have put that in the script, I should have had somebody say, “This is your get-out-of-jail-free card”. I might actually add that. That’s pretty good. I’ll credit you. Don’t worry. You’ll be okay.

Goodbyes for This Interview

JT: Well, man. That’s all I can think of, so thank you.

PB: Well, thank you. Yeah, I love just rambling on about the craft I spend my time doing. I am really glad you liked it. I can’t wait to share this with people. I’m just really proud of it. That’s the fun part of making the movie, for me. A lot of people when they’re done with it, have this postpartum depression. I go, “I love showing it to people and them experiencing it.”

Part of the fun thing about making movies to me is that there’s kind of this imagined world that exists. Even if it’s kind of a normal movie like Clueless or something. It still feels like [the] Clueless world. It’s just this weird [world]; they talk different, they look different. It feels different. With Reklaw, I created … this little outside world that other people can kind of buy into. The more people that see it, the more that they contribute to it in their head, and it exists. Just to talk about it as if these characters are real characters is a joy to me.

JT: Thank you very much, Polaris.

PB: Thank you.

Final Thoughts and Comments

After I pressed stop on the Zoom recording, I spoke with Banks some more for what felt like ages. I got to learn more about him, and him about myself. He is an incredible filmmaker who truly knows his craft. The man also knows a lot about popular culture. Of course, this has been shown in his short film and behind-the-scenes in this interview.

This year’s SXSW event has long ended, but you can still watch Reklaw on Mail Chimp!

For more crime, drama, mystery, thriller, and comedy-related news and reviews, follow The Cinema Spot on Twitter (@TheCinemaSpot) and Instagram (@thecinemaspot_). Also, you can now find us on Facebook (TheCinemaSpotFB)!

You can also check out our review of the film!

Managing editor & film and television critic with a Bachelor's of Arts in English Literature with a Writing Minor from the University of Guam. Currently in graduate school completing a Master's in English Literature.